‘Did you see the northern lights last night?’ My elder daughter asked in her text message from Toronto on the morning of May 11th. ‘I’ve seen tons of photos from my friends who just literally stepped into their backyards or onto their balconies and saw them clearly.’

It wasn’t that I hadn’t heard the prediction. Over the previous few days, the unusual sun storm activity had been in the news. There was concern that the powerful geomagnetic radiation could knock out electrical grids. But there was a prediction that the same electromagnetic forces would result in an unusually active aurora borealis. A spectacular show of the northern lights could extend deep into the continental USA.

The forecast for the Pacific Northwest was for clear skies and warm temperatures–– perfect viewing conditions for the “once-in-a-generation” celestial event. Yet beset by petty irritations, I collapsed on the sofa at 8:20 PM. I missed the show entirely.

Before reading my daughter’s message at 5:00 AM, I’d already seen the reports in the morning news. In every dazzling image there was a tiny sting. On a night when the northern horizon was pulsing with otherworldly colours–– I was a few metres away from the patio, snoring.

No wonder my daughter was surprised. She surely remembered the times when we drove out late to look for meteor showers. Sometimes we stood for hours shivering in a park, waiting for a few streaks of light. Yet neither she nor her two younger siblings had ever seen such starry skies as I had known in childhood. In my tiny village amid the woods of southwestern New Brunswick, moonless nights were pitch black. I cannot recall seeing the northern lights, but when the sky was clear, the firmament shimmered with countless stars… In rain-coast suburbia where my kids grew up, even the Big Dipper is rarely to be seen. Still, my kids enjoyed the rare opportunities we had to see a clear night sky.

My elder daughter seemed especially interested in identifying a few stars and taking in the more unusual celestial phenomena. In 1997, she was twelve when on several successive nights we saw the Hale Bopp comet. Even with the interference of the floodlights in the adjacent park, just after sunset it was as bright as Venus.

She was born around the same time that Halley’s Comet made its last appearance. That fact intrigued her even more than the coincidence of her birth and the discovery of the wreck of the Titanic. When she was just a few weeks old, I left her and her mother sleeping to view Halley’s Comet from outside the gates of the school compound in rural Zimbabwe where we lived at the time.

Of course, in its 1985 appearance, that legendary comet fell flat of predictions. As recalled from boyhood, it was supposed to be visible in daylight. Yet in the middle of the African night, it appeared no brighter than a faint and fuzzy star. Through binoculars, its tail looked like a ghostly flashlight beam. Yet that–– and its auspicious timing–– was enough to assure my daughter, years later, that Halley’s Comet had been magical to behold…

So with that personal history–– how could I not feel embarrassed in admitting that I had missed a rare celestial spectacle right above my doorstep? How could my daughter not but conclude that my curiosity was dimming with age?

‘I meant to see them but feel asleep,’ I texted her back. I will definitely make the effort tonight. Have to see the northern lights at least once before the really big sleep!’

She usually chided my morbid humour. But instead of the usual: ‘Com’on, don’t say that–– You’re not that old!’ she replied: ‘Well, better get out there tonight!’

That smarted. Still, I set my iPhone alarm for 11:15 PM. After a couple of fitful hours, I got up before it rang. Without waking my wife, I crept blearily outside and crossed the street to look for a patch of darkness on the Terry Fox High playing field. Unfortunately, the school security lights were as much a hindrance as the floodlights of the Chrysler dealership in the opposite direction. Not ready to give up, I returned home for the car keys. I drove 4 kms. northeast to the Pitt River dyke–– the closest place with minimal light pollution.

The usually secluded road through blueberry farms was lined with parked cars. The blaze of oncoming headlights was not encouraging. As another car pulled out to leave, I took its space then walked past the streetlights onto the dyke. On the pathway along the river, cell phones glowed in both directions. I headed northward, past a long line of silhouettes. There were giggling teens and parents carrying kids. There were older folks in lawn chairs and even a few serious sky-watchers bent over tripods. More Chinese than English was heard in the low voices. A few hundred metres from the entrance gate, the crowd thinned out and it became sufficiently dark to see the stars. For about fifteen minutes I gazed up into the northern sky.

There was nary an unusual flicker. Either my timing was unlucky or the once-in-a-generation light-show had been a one-night stand….

The sting of missing the aurora borealis would not have been so sharp if it hadn’t been the second once-in-a-generation celestial spectacle missed within a month.…

In driving back, I thought of the total eclipse of the sun which millions of North Americans witnessed on April 8th. After reports of the spectacular eclipse, I regretted not making a brief trip back east to see it–– a notion I’d toyed with back in January.

During the eclipse, my daughter FaceTimed to show the view outside her duplex. Although Toronto was outside the path of totality, the mid-day twilight looked spooky… Meanwhile on our wet west coast, the tiny corner of the moon’s silhouette brushing the sun would scarcely have been noticed even if it hadn’t been raining.

According to NASA, the next total eclipse potentially visible in daylight from land will be in August, 2026. Its path of totality will only be through Greenland, Iceland and Spain. The next solar eclipse potentially observable from British Columbia won’t be until August, 2044. Whatever remains of me by then (far more likely dust than flesh) will still be well outside the path of totality… However grateful for having experienced well more than my share of wonders over the decades––plainly, a total solar eclipse will never be among them.

Still, there is consolation in having seen a partial eclipse in a rather exotic setting. That was in Tanzania in February, 1980. Yet even the memory of that one taunts because its totality was so narrowly missed.

At the time, I was teaching in the Kilimanjaro district which was directly in the path of totality. Yet on the day of the spectacle, I was on an assignment in Morogoro, more than 500 kms. to the south. In the partial eclipse at that locale, confused monkeys hooted in midday twilight. Yet upon return to my school, I heard reports of stars shining at noon over the (then) glacial dome of Kilimanjaro. The peep-show in Morogoro had been a feeble semblance of the lollapalooza missed…

In pre-retirement years, such recollections especially haunted after hard days in the grind. Stuck in traffic after struggling to gain the trust of unhappy students too often seemed like due punishment. What else was to be expected from work misaligned with aptitude––and far from the heart’s desire?

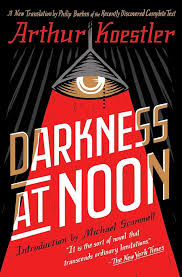

Amid such dark thoughts, I was sometimes reminded of a passage from Arthur Koestler’s ‘Darkness at Noon.’ Near the end of that gloomy novel of betrayal and disillusionment, the old Bolshevik called Rubashov, awaits execution after being framed for treason. An anonymous fellow prisoner with whom he communicates through knocks on the cell wall, taps out a question: ‘What would you do if you were pardoned?’

After thinking it over, Rubashov taps out his reply: ‘Study astronomy’.

Recalling that passage provided solace that unlike Rubashov–– I was still slogging towards a pension and a possible second act. In imagining a fruitful post-retirement, a modest pursuit of astronomy seemed to offer redemption.

Although in my first months of ‘freedom’ it was solitary hiking that proved most redemptive–– I did obtain star maps and a dictionary on astrological terminology. I even started a MOOC [on line course] on astronomy. But by the end of the first year, the star maps were gathering dust and I’d dropped the course. The science was fascinating (even to my limited comprehension) but the hard science was not what I was after. I neither had the patience for mastering a telescope. The notion of hunching over a tripod on a cold night was just too remote from the simple hope of reigniting a child-like wonderment in the mysterious cosmos…

Among the swirl of insomniac thoughts that accompanied my return to bed, was the coincidence that that the province of New Brunswick had been so favoured by the celestial spectacles I’d missed. News sites had shown photos taken there of both the April eclipse and the spectacular aurora just thirty six hours before. It occurred that a particular boyhood friend–– long out of touch––would have been especially delighted by that celestial treat.

RM had stayed on in the native village. Now past his mid-seventies, he was still living in the house of his childhood. He hated travel and eschewed technologies, post LP records. Yet he had always been a serious reader. In insisting that he was missing nothing of importance to him, he once quoted Samuel Johnson: ‘When a man is tired of London, he is tired of life; for there is in London all that life can afford’ No matter that RM’s ‘London’ was a backwater even in a tiny province. He insisted he was content.

Whether or not he ever had midnight terrors about a possibly wasted life–– the recent celestial phenomena may well have struck RM as a profound vindication. Twice within a few weeks, he had had on his village doorstep, a ringside seat to two rare astronomical splendours. Meanwhile, those who were by nature restless and impatient; those who chased chimera to the ends of the earth–– they miss the really big events… It was not hard to imagine his smug smile…

I slept in until nearly 6:00 AM. In checking morning messages, the first one I saw was from my elder daughter. ‘Did you take any photos?’ she asked. ‘I went down to the dyke for a hour or so,’ I texted back. ‘But there was nothing to see.’

When I got back from fixing a cup of tea, she had already replied: ‘Well, at least you tried!’

I took that as her acknowledgement that my inner star was still blinking. It was more than enough consolation…

2024, June

Ad. Note:

On the clear night of October 11th at 12:20 AM, I stumbled up from the couch and drove to the north side of the nearby school playing field. I walked to mid-field as my eyes slowly adjusted to the dark. Against the starry background, wavering white light was faintly visible. I took an iPhone pic photo. Lo and behold––the sky above the silhouetted trees showed bands of green and rose…

So, in some consolation from the disappointment of last May–– I can claim to have beheld the northern lights once. At least my iPhone did…

Leave a comment