Ghosts sometimes perch at my shoulder as I take notes for my journals. However disquieting their whispers–– they are never to be ignored. Notable among such ghosts are those of a few characters briefly encountered nearly half a century ago:

In 1975, I worked on a social service project in the Vancouver Fairview neighbourhood. Our eight-person team were mostly liberal arts grads in our early twenties on an extended gap year. The project was essentially a time-biding offering of the left-leaning provincial government for youth like us…

We called ourselves the ‘Health Assistance Resource Team’. None of our team had any training in health care or even in social work–– but we liked the catchy acronym (HART). The posters we pinned up in neighbourhood laundromats and community bulletin boards featured a big red heart logo.

We worked out of a a church basement room on West 12th Ave. We did house cleaning, yard work and moving jobs. We ran errands for the housebound. Although our service was targeted to low-income seniors, in order to maximize our reporting-out stats––we attended to just about anyone who called our number.

At first, many of our referrals came from social workers at the nearby Vancouver General Hospital. They usually requested assistance for recently discharged patients. A few such requests were for escorting particularly vulnerable patients.

A few times I accompanied to the airport, released patients who might have otherwise disappeared back into the city’s skid row. One was a First Nations’ fellow whose forehead was stitched up like Frankenstein’s. He told me he’d been in an axe fight–– which he’d won. He was not keen to fly back to his remote village in the far north. It took considerable cajoling to get him through the gate.

Even more memorable was the escort call out for a discharged schizophrenic called W.B. Waring. Years after our brief encounter, his name reappeared on a yellow HART referral slip that turned up in a box of old papers…

Before meeting him at the hospital, I had collected his backpack from a skid row hotel room. With a note and confirming phone call from the social worker, the desk clerk had given me fifteen minutes access to the fetid cubicle. The backpack was beside the filthy cot. Hurriedly, I shoved into it his scattered clothes. Almost overlooked in the corner of the plywood wardrobe were a pack of Tarot cards. Creepily enough, I was also into Tarot at the time.

Yet more creepy was the thick orange scribbler. In it were drawings of demons: horned, multi-limbed and baleful-eyed. Under some of the drawings were weird captions (‘it’s squeezing my eyes!’) and word strings, nearly indecipherable. With a shiver, I stuffed the notebook and the deck of cards in the backpack…

Back at the hospital, W.B. Waring was slouched in a chair before the social service counter. He was about my own age, slight of build with long stringy hair and smeared glasses. He ignored me while the cheery social worker handed over the taxi vouchers and his plane ticket. The Ministry of Human Resources wisely understood that it would take more than a bus ticket to ensure he got back to his native Saskatchewan–– presuming that province would relieve British Columbia of his further care…

In the taxi to the airport, Waring looked silently out the rear window. Sitting beside him, I was tempted to ask him about the Tarot cards or even to compliment his drawings. That seemed risky so I made small talk. His nods confirmed he was listening. Had I not known he was schizophrenic–– I would have thought him merely shy.

He seemed present of mind until we sat down near the departure gate. When I asked about weather in Saskatchewan, he seemed to slip into a trance. His eyes rolled back and he began gently swaying, heedless of the smouldering cigarette in his yellow fingers… Watching him, I felt something of the mesmerizing fear of a weaving cobra.

Fortunately, the flight to Regina was soon called. The last I saw of Waring, he was fumbling open his backpack in the security check…

In the taxi back to the HART office, it struck me that if I ever wound up in hospital–– or worse–– someone would also have to gather up my paltry belongings from my rooming house. What would a stranger make of my diary? The diary of Arthur Bremer, who crippled George Wallace in an assassination attempt, had recently been published. Of course, there was no imaginable scenario by which such lurid attention would ever fall upon my journals. Yet the fact that psychopathic loners often keep diaries was still jarring…

Another unforgettable hospital call-out was for escorting a kidney dialysis patient on a break back to his bed-sitting room. The encounter left such an impact that I took notes of it that night:

The patient was waiting beside his social worker in the hospital lobby. When she introduced us, Frank Horner put one of his canes under his arm and limply shook my hand. He was in his early thirties but his face looked older. His flabby chin was shivering. More startlingly–– his head appeared unusually small for his body.

After the smiling social worker departed, we walked–– rather hobbled–– to the taxi. Grunting, Horner did not resist my guiding arm. He didn’t speak until we neared his rooming house. We were both in the back seat.

“I just gotta check my stuff. I don’t trust some the guys at my place.” The slightly whiny voice fit his doleful look.

The hobble was repeated from the curb to the front steps of a rooming house which looked marked for demolition. Midway up the front steps, he sank down to catch his breath. He then pulled off his glasses and rubbed his mottled face.

“If it’s not a bother,” he said with a hint of self-pity, “you can come in for a cup of coffee.”

On the phone, the social worker said that he was “a little depressed.” She suggested that a short visit could take his mind off the treatments.

“Sure,” I said, feigning that the choice was voluntary.

We first went to the kitchen. It was as dismal as any shared by transient working men.

Leaning forward on his crutches, Horner pointed to ‘his’ cupboard door. I opened it to get the jar of instant coffee. Spying the box of Shreddies therein, he asked me to hand it down. He softly shook the cereal box then shoved his hand inside.

“When I went into the hospital last Wednesday, this was full––full! Can you believe it?” Following his dismissive gesture, I put the box out of his sight.

With a ‘tsk’, he then hobbled round to the fridge. He peered inside.

“I shoulda known. I had a two-quart carton of milk in there last Wednesday. Disappeared! The buggers around here,” he muttered. “You’d think they’d have a little sympathy.”

He insisted that he never drank coffee black but asked if I still wanted some. I declined. He then asked if I could accompany him up to his room. He needed a witness, he said, in case any of his property had been disturbed. I assented.

As he laboured up the stairs to the second floor I stood behind, lest he fall backwards. His room was at the end of the dank hallway. With a grimace, he fished the key from his loose trousers and opened the door.

“Looks OK,” he muttered.

The room was spartan but tidy. Beside the single bed was a dresser and a plain desk, stacked with books and papers. On the dresser was a plush koala bear. On the windowsill was a flag.

Recognizing the Union Jack with the blue background, I asked if it was the flag of Australia.

“It sure is,” he smiled. “I lived there five years. Best years of my life!” Still smiling, he sat down on the edge of his bed. “I could tell you tales!”

Leaning on his cane for about fifteen minutes, he told his story:

He hailed from Winnipeg but could neither get along with his family nor stand the winters there. He burned bridges in his early twenties and arrived in Vancouver. He said he drove a taxi for a few years then took a passage by freighter from Vancouver to Sydney.

From painting decks in route, he did odds job in Sydney but saved enough for travelling around. He hitch-hiked north to Queensland and south to Tasmania. Still, when the laws for Australian citizenship got tighter, he had to come back to Canada to reapply for a residence permit. He never got the chance.

“Since I got back here last year,” he slowly shook his head, “I’ve had nothin’ but bad luck.”

Capping his misfortune was the crushing diagnosis of failing kidneys.

“Haven’t been able to work–- had to go on welfare. Only moved into this awful place because it’s cheap and close to the hospital…” His eyes turned glumly downwards.

I broke the silence by asking about the big book prominent on the desk. It looked like a photo album with a plain black cover. I asked if it contained photos of Australia.

He perked up and turned aside. “No, there’s no pictures in there.” He hesitated, then asked softly: “Ever heard of automatic writing?”

Only vaguely, I told him.

“Let me show you,” he said.

He pushed himself up with his canes then leaned over the desk. Carefully, he opened the thick cover. Before turning the first page, he told me that he was a practitioner of what he called “the science of automatic writing.” He said that his late grandmother had first demonstrated it for him. She apparently had been a spiritualist who had held seances in rural Manitoba in the early century…

When he gently turned the first page, I leaned closer to read the script. In a florid hand was the title: ‘The Secret Writings of Franklin de Soiree’.

“That’s me,” he responded to my quizzical look. “But it’s not really me. It’s the character who moves my hand when I do automatic writing.” His voice became softer. “I go into a kind of trance. Franklin de Soiree takes messages.”

Catching my dubious look, he chuckled. “I know that sounds crazy to some people–– but it really happens. Look––nearly half the book is full!” He turned the pages too quickly for me to catch any of his messages from the beyond…

I was a little spooked–– but still curious to hear more. Yet I reminded myself that I was only assigned to escort a vulnerable patient. The call out was scheduled for an hour and the time was almost up……

“Wish I could stay longer,” I said. “But I have to get back to my office.”

“Sure,” said the alter ego of Franklin de Soiree, in shrinking back to the mousy Frank Horner.

I don’t remember whether there was any other call-out to assist Frank Horner. If another member of the HART team had taken such a referral, I don’t recall mention of it.

One supposes that not long thereafter, he had had his final dialysis treatments. His social worker had implied that his time was short.

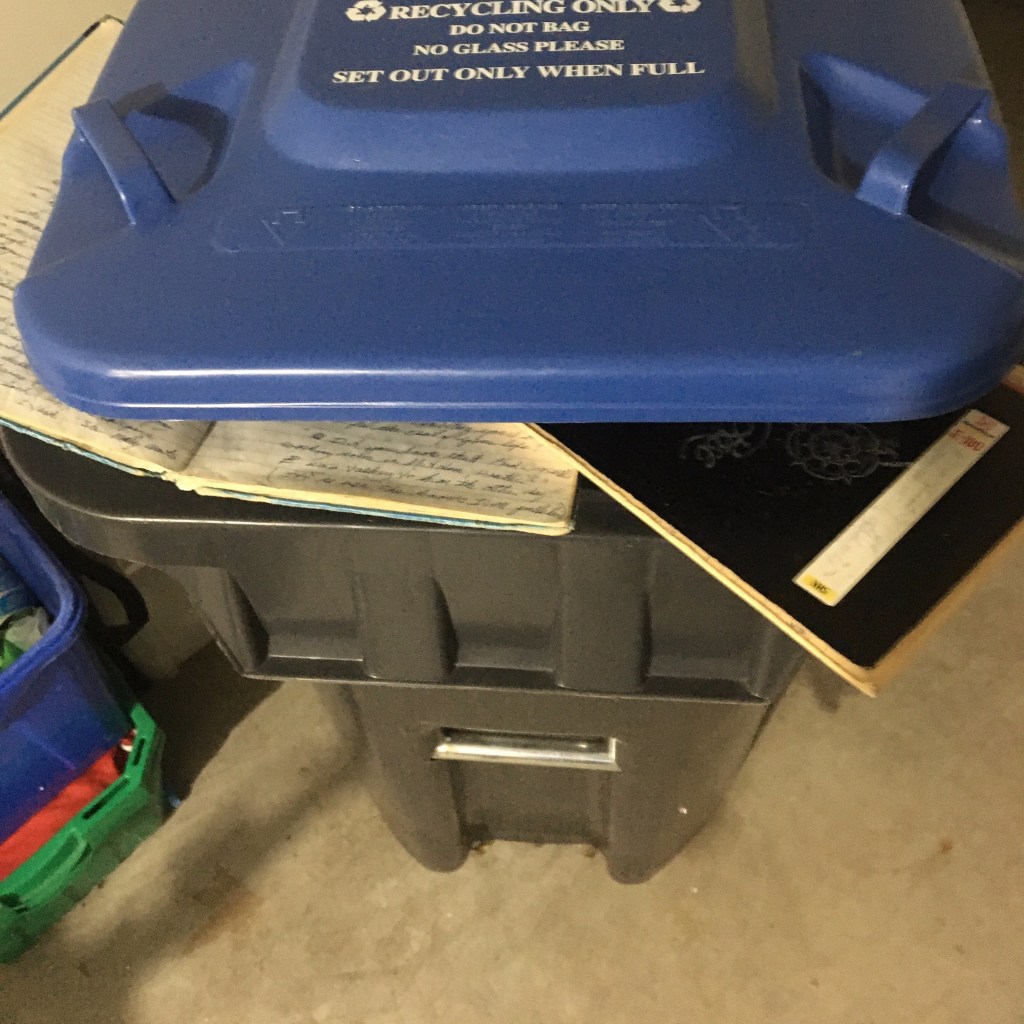

A half century later, I wonder what ever became of his secret writings. Since Horner said he had no family or close friends in Vancouver, someone would have been tasked by social services to clean out his room. Very likely, the revelations of Franklin De Soiree would have been tossed into a trash bag with hardly a second glance…

One more ghostly presence that endures from 1975 is the secret author of an unpublished guide on ladylike etiquette. She was in her mid-seventies and had apparently lived alone in a dingy bed-setter for indeterminable years. Finally, her turn came up for a suite in an assisted living complex. The HART team was called to assist in her move.

Her worldly belongings–– except for her rocking chair––fit into no more than a half dozen cardboard boxes. A female co-worker and I helped pack them before driving her and her things to her new suite. While we crouched on the floor of her old room with paper tape and scissors, the tiny old lady smiled from her rocking chair in the corner. She was delighted to be moving.

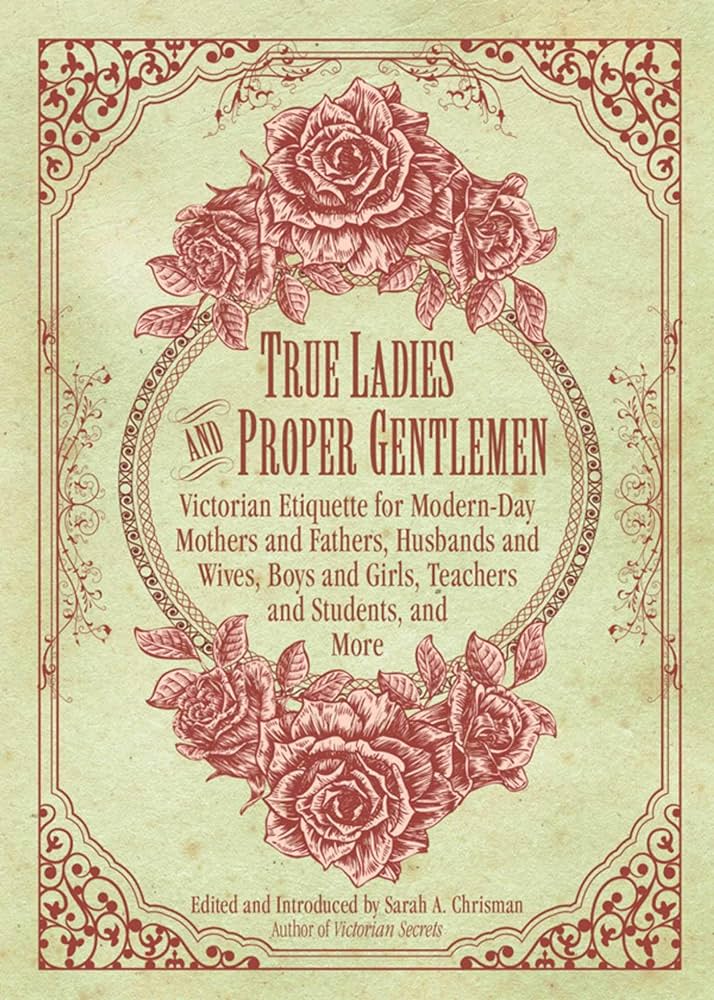

Meanwhile, in preparing to load the boxes into my coworker’s sedan, a notebook with a light blue cover caught our attention. My co-worker tilted it up. Meticulously printed on the cover was: ‘Manners for Modern Girls’.

“Mind if we take a look?” my co-worker asked the old lady. Gently rocking, she nodded.

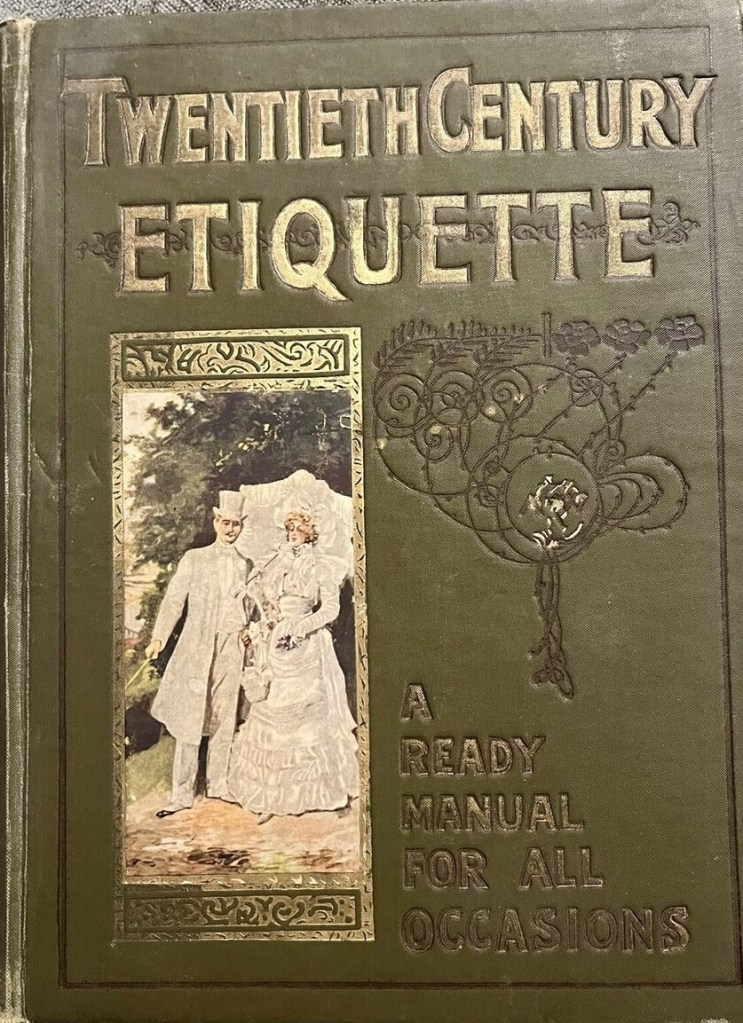

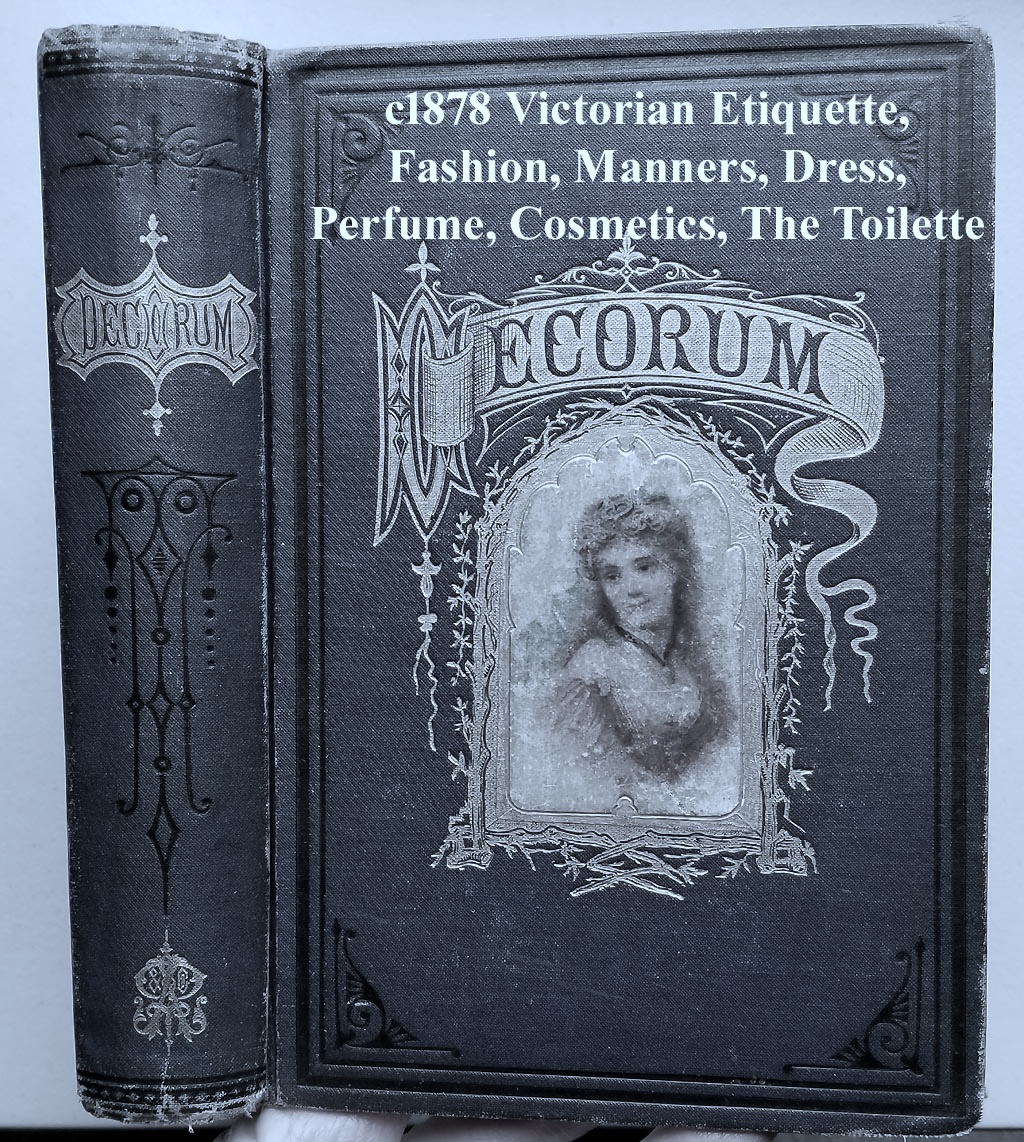

My coworker slowly leafed through the notebook. I leaned closer to read over her shoulder. Every page was neatly hand-printed. The self-made guide was divided into chapters with such titles as: ’table manners’, ‘ladylike posture’ and ‘proper attire’. There was even a chapter on ‘demeanour with young Christian gentlemen.’ While there were no illustrations–– Victorian lithographs would have been appropriate.

My co-worker closed the cover and looked solemnly round at the old lady. “Is this all your own work?”

Bashfully. she looked down, She has spoken very little since our arrival, but her box of books was evidence of an active mind.

“It’s wonderful,” said my co-worker. “So well organized!”

The young woman was innocently patronizing. Braless girls of the 1970s would have regarded a manners’ guide to a bygone world that predated Emily Post as parody, at best.

Still, the old woman glowed in the moment of attention. “It’s just my little something,” she smiled.

“It must have taken you ages,” gushed the young woman.

The old lady chuckled. “O, I just worked on it bit by bit. It keeps my fingers limber.”

My co-worker cooed on about writing workshops for seniors. She said she would try to put the old lady in touch with one.

The old woman nodded dutifully. Were she ever to have written an etiquette guide for old girls–– a demeanour of polite deference would surely have been emphasised…

Several decades later, that old lady came to mind when I was weighing the fate of my old notebooks. To what extent were my early writings similar to ‘Manners for Modern Girls’? Could my ‘precious’ pieces not be as fossilized–– and my imagined audience as much a figment of the past–– as that of the old woman’s?

Such taunting thoughts led to the tossing away of the bulk of my accumulated papers. The rescued bits I transcribed in digital form. During that process, at least one of the three ghosts of 1975 were usually present…

As for the fate of that little social service project of nearly a half century ago:

When the social democratic provincial government dramatically lost its re-election bid in December of 1975, the incoming ‘free-enterprise’ government slashed the Human Resources budget. “Dubious make-work projects” were the first services to be cut.

By the time the defunded HART project was dissolved, I had already blown town. My getaway was not via a freighter to Sydney–– but by bus down the Gringo Trail…

-2024, July

Leave a comment