GMJ, a Professor of Education whom I had the pleasure of knowing in the 1980s-1990s, was a gifted raconteur. An immigrant from Wales, he had a sonorous voice and a sharp wit. A couple of times over “pints” (he preferred Britishisms) at the university pub, I heard his tales of teaching high school English in the B.C. hinterland in the 1960s-1970s. Rather like the Robin Williams character in ‘the Dead Poet’s Society’, he apparently rocked the boat with inspired classroom performances. Outside of teaching, he and his former wife raised goats on a hobby farm and did a hippie-era quota of hallucinogens…

I missed hearing of his death in 2012 at only sixty-nine. I found out two years afterwards through a reference to a memorial bursary in his name that popped up in his university’s online newsletter. Saddened, I looked up his obit. It included several heart-felt tributes from former students and colleagues.

In further searching of his name, I was not surprised by the paucity of links to publications in academic journals. Relatively late in getting a doctorate, he largely built his stellar career around student-teacher instruction and program management. Yet it was interesting to discover his numerous links to the Vancouver Welsh Society and the Dylan Thomas Circle. I knew that he wrote a little poetry but was unaware how much affinity he had for the much-lauded Welsh drinker and bard. That was plain from ‘At the Mercy of Words: Dylan Thomas and the Welsh Poetic Tradition’. That was the only full-length text of his authorship I could find on the internet.

Posted in PDF format, that essay was probably never published in any journal. The undated on-line copy appears to have been scanned from double-sided typewritten pages. Given the subject, one might almost have expected whisky glass rings–– like watermarks–– on the pages.

I thought of that essay recently after rereading Thomas’: ‘Death shall have no dominion’. When my son revealed he was devastated by the breakup with a long-term girlfriend, I suggested that poem might ease his self-torment (‘Though lovers be lost love shall not/ And death shall have no dominion’). Thereafter, I looked up GMJ’s essay again and read it more carefully.

GMJ makes a case that while Dylan Thomas wrote in English, the rhythms of his poetry are deeply resonant of Welsh… He also claims that Thomas’ early influences were very similar to his own. That background was rooted in the Welsh language and in the folkways of Welsh villages and their surrounding countryside. In describing his own village where he grew up in the early 1950s, he writes: ‘In Llanfihangel the whole soundscape was Welsh, and you could easily go all year and never hear a word of English…’.

GMJ’s mother tongue was English but he was bilingual from childhood. In his essay, he claims that his “soundscape” was deeply enriched by the Welsh his father spoke and which he heard beyond his home: “The sounds and cadences of Welsh, heard in the chapel, in school, on the farms, at concerts and eisteddfodau took over my sonic imagination…’

In the semi-rural Wales that GMJ recalls, poetry was apparently beloved by all. In the eisteddfod (traditional Welsh festivals of the arts) he describes–– neither social rank nor formal education was any barrier to competitions in poetry recitation:

The farm worker or farm maid would go to chapel every Sunday, where their great great grandparents had learned to read before the arrival of state schooling. Many would also take part in the local ‘eisteddfodau’ where the country bards would try out their stuff in fervent competition. Also, it was not unusual for a farmer or a quarryman to compete and sometimes win at the highest competitive level.’

I read that paragraph in both admiration and envy. I marvelled at the advantages of those who are nurtured in both a world language and a much more intimate native tongue. At the same time, I imagined that communicating in a native language harmonized over centuries to a common landscape would afford subtleties unfathomable in a global language.

Such a rich linguistic endowment could not but remind me of the poverty of my own…

The world of my infancy in southwestern New Brunswick in the early 1960s was shaped and limited only by English. Like any child, I assumed my native language was universal–– that through it, the world was entirely accessible. I was blind to the fact that the mere two hundred years in which my transplanted language encroached upon that territory was not time enough for it to harmonize with the ancient spirits of the land.

Still, two centuries of settlement was long enough to give rise to a local dialect. The English of semi-rural southwestern New Brunswick as I recall it–– was more distinct than it probably is today. Its native speakers typically mumbled or droned words through their noses. More reticent folk tended to communicate with grunts and sighs–– if not through gloomy silences… By my adolescence, the local accent sounded as dreary as the whine of a chainsaw in winter.

As for languages spoken in that territory eons before the arrival of Europeans–– only their traces remained in a few bastardized names of local lakes and rivers. Among my fellow tribesmen, there was little curiosity about those very oldest names of things conferred upon the local landscape. The echoes of those words were heard only by a few descendants of the Passamaquoddy–– none of whom lived in my home village…

I also grew to adolescence with scarcely any exposure to Acadian French. Still, I was always at odds with the hostility often expressed by many locals towards the rival tribe who dominated the north and east of the province. It is notable that many fellow native unilinguals would have been challenged in communication elsewhere in the English-speaking world….

Roughly considered, that was the ‘soundscape’ upon which my brain was initially wired…

GMJ once joked that a son’s marriage to a Catholic would be less shocking to a Welsh protestant family than a marriage to a girl of another race. Until reading his essay, I would have thought mainstream religion to be at odds with his intellectual bent. Yet he pays homage to the Wesleyan church and the Welsh bible in nurturing of the language he so deeply loved:

‘…there was a Bible in every home and it would be read, silently and aloud, in the kitchen as well as in the chapel. Its verses, memorized by generations of Welsh children, formed the backbone of a living popular intellectual tradition…’

My childhood village and its many churches could have been on a different planet. Sunday morning in the Church of England I was compelled to attend was like a weekly dunking in cold water. I can’t imagine how any child could conceive of the purpose of squatting, standing and sitting for two hours in response to indecipherable droning. The only other sounds recalled during the service were geriatric coughs and sour notes of the church organ. Long before sexual awakening, I sensed that church was designed for detumescence of any awe of the imponderable.

Squeezed into a pew, I would typically fidget through the Book of Common Prayer–– back and forth–– from Baptism to Burial of the Dead. Its pages (faintly redolent of moth ball) made plain that the mortal coil was short–– rather like the life of Solomon Grundy in the nursery rhyme. The proscribed duty seemed to be getting through the stages of mortality without drama or fuss. The tone of delivery of that message was reminiscent of a grandmotherly scolding: ‘Don’t think you’re special. This is the best you can hope for, too!’

More than six decades on, I am grateful for having been spared such memes which could have been implanted by the village’s viler cults––notably the Catholic or the Pentecostal churches. Still, it is hard to conceive of a religious orientation more remote from a ‘popular intellectual tradition’ than that afforded by the Anglican Church of Canada…

In the reading the descriptions of the Welsh eisteddfod, I tried to recall any comparable festival from my home village…

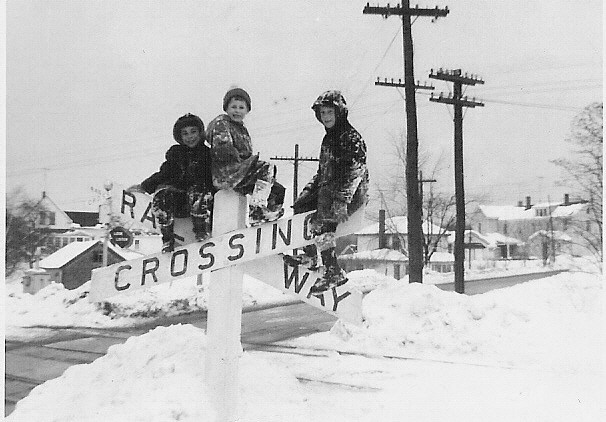

The only celebration of local arts culture I could remember were variety shows attended in the school gym/auditorium in the early 1960s. Held in late spring or before Christmas, those special shows featured local talent of all ages.

Among the regular performances was that of a baritone Baptist father and his three children. In matching bowties, they swayed reverentially while crooning ‘spiritual’ standards like ‘Rock of Ages’… Then there was the local light who sang Hank Snow tunes while showing off his guitar-picking with a gap-toothed grin. His yodeling got the most enthusiastic applause. Another regular was the forever young pianist who thumped out bright marches from his wheelchair. His broad forehead softly nodded to the whistles of encouragement…

The variety shows usually included a couple of dancing acts. Teens in cowgirl hats would tap-dance to tinny music, or one in a kilt might hop back and forth over a wooden sword. The audience rhythmically clapped–– perhaps uneasy as to whether that was a proper ‘traditional’ response.

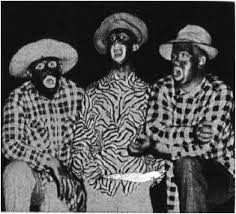

A showstopper clearly remembered–– was a comic performance by three prominent villagers. The usually serious men appeared in shabby overalls and straw hats. Their lips were reddened and faces shiny with black shoe-polish. They sang ‘O Susanna’, and other cotton-pickin’ tunes, accompanying themselves on washboard and rubber band bass. In pauses between verses, they exchanged Amos n’ Andy-style banter. Their exaggerated drawls had the audience howling with delight.

Would GMJ have recalled any Eisteddfod performers ever appearing in blackface?

It was not that my native territory was bereft of any original artistry. The nationally renowned fiddler, Don Messer, hailed from a hamlet just a stone’s throw from the village. Yet curiously, no fiddlers performed in the variety concerts I remember.

I can neither remember hearing music performed in a “kitchen party” for which some communities in the Canadian Maritimes were renowned. There were a few talented guitarists among my teen cohort, but they brought bottles–– not their guitars–– to house parties.

It is hard to identify a single distinct feature of the local culture, as I recall it. Despite the ‘proudly English’ sentiment, there was no echo of a mummer’s procession in the village doll carriage parades. In the Christmas Eve gathering for Santa’s arrival in a firetruck, there was no hint of wassailing…

A late friend who grew up on rural Kentucky and I used to joke about how much our respective cultures had in common. In many more tendencies than predilection for ole time religion and country music––rural Maritimers seemed to be the northern cousins of Appalachian hillbillies.

Among the more bizarre commonalities we noted was a morbid voyeurism. We both remembered standing with fellow villagers behind the local garage viewing newly wrecked cars (More than one recalled had blood spatter or hair clots on the seats). Perhaps such a custom reflects a community effort to absorb tragedy and grief. To be less charitable, the practice hints of deep-seated boredom and a need for sadistic arousal…

Of course, such grisly voyeurism might be a feature of isolated communities everywhere. A girl I once knew who grew up in Mount Isa, Queensland, spoke of local teens habitually sneaking into the hospital to view the brain-dead patients… More anecdotal evidence coming to mind includes a crowd watching a seagull caught on a fishing line in Port Alberni, BC and one ogling a stray dog with firecrackers tied to its tail in Macon, Georgia…

I wonder whether such sadistic voyeurism is a feature of cultural poverty or of human nature in general… Despite their enlightened Eisteddfod festivals, it would have been interesting to know whether Welsh villagers also gathered before house fires and car wrecks…

GMJ ends his essay with his own Welsh translation of ‘Fern Hill’… He claims that even a listener who knows not a single word of Welsh but who is familiar with the English rhythms of the poem will recognize the rhythms in the Welsh version… Even though Dylan Thomas apparently knew little Welsh, GMJ asserts: ‘I am convinced that Dylan is a Welsh language poet writing in English.’

That conclusion, just in the first reading of the essay, left me uneasy… A prerequisite of a properly nurturing ‘soundscape’ was almost as intimating as Ezra Pound’s insistence that knowledge of Attic Greek was a minimal requirement for the writing of poetry in English… Yet amazingly enough–– even the ‘tone deaf’ and semi-literate are sometimes given to poetic self-expression. Such a world of wonders it is, indeed…

Back in the early 1990s when I was taking graduate courses at the local university, I would sometimes stop before GMJ’s open office door for a chat. One day I found him sitting before his Power Macintosh, unusually glum. I asked him if he was feeling OK.

“The buggers,” he said, nodding at the open parcel on his desk. “I just got a rejection slip with the book of poetry I’d submitted. I had hopes for that manuscript!”

“I know how that feels,” I said without elaborating.

He sighed. “O well, maybe–– maybe I should just send it forth into cyberspace. Just send it out there–– see where it lands. What do you think, F.?”

I told him that that did not seem such a bad idea…

Whether or not he did post those poems somewhere online–– none of it comes up in a Google search under his name. Perhaps he posted them anonymously–– just as do I with these very words…

I will keep looking….

-2024, December

Leave a comment