‘The Meaning of Monty Python’ (2013) features the five surviving Pythons––Cleese, Gilliam, Idle, Jones and Palin–– in conversation over tea in a living room setting. The documentary bookended the Turner Classic movie channel’s recent tribute to the legendary troupe. Shown before the documentary were ‘Monty Python and the Holy Grail’ (1975), ‘The Life of Brian’ (1979) and films of live performances. Vintage Pythonesque comedy never fails to charm…

The discussion among the elderly Pythons shifts intermittently from the frivolous to the philosophical. A notable topic was the changing character of comedy over the half century since their BBC TV debut. The Pythons observed that the British class structure they once wildly lampooned has radically changed. Upper-class twits and indecipherable cockneys now seem historical oddities rather than fodder for satire. British musical hall parody seems even more dated.

The younger Pythons were not overtly political. They did not deal with the hot button issues of Britain in their heyday: there was no parody of conservative attitudes to immigration, labour strife or the troubles in Ireland. Their social satire was not pointedly from the left…

Still, they skewered the most sacred cow of all. ‘The Life of Brian’ (1979) is a masterwork in satirically nailing the dubious origins of Christianity. Little surprise that ‘Always Look on the Bright Side of Life,’ sung from from a phalanx of crosses in the final scene of the unwilling messiah’s crucifixion, is today often requested to be played at funerals. Even more uproarious is the brilliantly choreographed musical sketch, ‘Every Sperm is Sacred’, from ‘The Meaning of Life’ (1983). It should be required viewing at every papal enclave.

Older fans will remember the 1960s’ ‘Monty Python Flying Circus’ skit in which gossiping British judges disrobed to reveal lacy undergarments. Then there was the bureaucrat traipsing from the ‘Ministry of Silly Walks’. One might wonder how a mainstream audience (if such a thing still exists) would react to such humour today.

As recorded in the 2013 documentary, the septuagenarian Pythons lament the dearth of creative satire. While ‘cancel culture’––is routinely excoriated from the right, its (mostly male) comics tend to be more vicious than funny. In the view of John Cleese, an open licence for raunchiness does not compensate for the self-censoring worry about causing offence to “oversensitive communities…”

Soon after the remarks about contemporary sensitivities, Terry Jones, the Python history buff, mentions Wittgenstein. For me, that reference recalled the Python skit in which German philosophers take on the ancient Greeks in a football match. Yet the elderly Python conversation moves from Ludwig, the philosopher, to his brother Paul Wittgenstein, who was a one-armed pianist. That gives rise to both muted chuckling and head ducking…. That little turn of awkwardness reminded me of Python skits that involved amputated limbs:

There was the Zulu War skit in ‘The Meaning of Life’ in which a British officer (Eric Idle) sits in a field tent calmly reading a book with one leg stretched out. The other is missing. “No worries–– you’ll be right as rain in a few days,” says the military doctor (Graham Chapman) in plumy accent, while tapping the bloody stump with the stem of his pipe.

More memorable was the Black Knight in ‘Monty Python and The Holy Grail’ (1975). Triply amputated by King Arthur’s sword, he refuses to surrender.“’Tis but a scratch!” says the armless knight, head-butting the king while hopping around him on his last limb.

Then there was the skit in which Cleese appears as a World War One soldier with both sleeves pinned up to the shoulders. When the commanding officer (the inimitable Chapman) comes to the trench to have the soldiers draw lots–– the armless one coolly pulls out his straw with his teeth.

In recalling those skits, I also remembered that Paul Wittgenstein lost his right arm in the First World War. In Python world––might the spectacle of him playing piano be roughly half as amusing as that of the armless Black Knight?

While proudly of the generation who once regarded the Python troupe as ‘the Beatles of comedy’–– I must admit that in the same era, I found the amputation skits disarming. They were funny–– but embarrassing. Even in the dark of a movie theatre, I dreaded that others would assume I was offended. Yet the spectacle of the armless Black Knight undeniably triggered a self-consciousness of my own empty sleeve…

Such embarrassment was not confined to Python skits. A reference to a slot machine as a ‘one-armed bandit’ had a similar effect. More dreaded were the rare appearances of arm amputees in movies or on TV. In watching the TV series ‘The Fugitive’ in my mid-teens, I was habitually braced for references to Richard Kimball’s wife’s real killer: the one-armed man. Most jarring were the episodes in which he appeared: right sleeve pinned up, fleeing into the shadows.

Such unease was not confined to my youth. In the early 1990s, I dreaded staffroom chatter about the then-popular TV series, ‘Twin Peaks’–– a few episodes of which featured a creepy one-armed man. Then just a few years ago, I was unexpectedly jarred by a scene from ‘The Last Waltz,’ the documentary of the final concert of the Band. In an interview segment, a grinning Robbie Robertson told an anecdote of the roughness of his iconic group’s early days. He described playing a Texas night club in the early 1960s that was so sleazy: “the go-go dancer had only one arm!”

However sordid that imagining, I am not offended by its summoning as dark humour. The shock of unexpectedly encountering physical abnormality is a natural human reaction. Perhaps too, is easing the awkwardness by later making light of it. Indeed, the most awkward reaction is pretending not to notice. In belonging to a certain ‘visible minority’ myself––I understand that in a distinctly personal manner.

In the otherwise forgettable Mike Myers’ comedy ‘Goldmember’ (2002), there is a scene in which the Austin Powers character is confronted by a secret agent with an abnormally large mole on his face. The agent declares he is perfectly aware of the irony of both being ‘a mole’ and having a huge mole above his lip. “No one would make that connection!” says Powers with an excruciating grin.

Fortunately, for a real person with such a mole–– friends, family or colleagues would hardly notice it. That is the mercy of habituation. After a few exposures to the mole, even a buffoon like Austin Powers would no longer be awkward around it…

Understandably, a large facial mole is less likely to cause unease than is an unexpected missing limb. But then an empty sleeve–– even a hook–– is apt to receive fewer stolen glances than a face like that of Joseph Merrick, the unfortunate Victorian-era ‘Elephant Man.’

After more than sixty years, I find it difficult to completely ignore the surprise that occasionally attends my unexpected appearance. Still, furtive stares from strangers are less annoying than bird shit on the windshield. Dealing with patronization in more personal encounters, however, is a much bigger pain in the ass. I suspect that many others so exposed feel similarly. Having no personal contacts with those who share in this singular annoyance–– I can only speculate about their reactions.

My only ‘community’ is the suburban neighbourhood where I walk my dog. Therein I know more names of pooches than those of their masters. I suppose I am often recognized by my dummy hand––which is hardly more life-like than any joke shop artifact. Yet over the last decade, I have appeared regularly enough to be treated as any other invisible codger.

My inclination has always been to ‘pass’ as anyone with the four-limbed bauplan. That inclination is not without awareness of the dark historical connotation of ‘passing’. Fortunately, those once self-abnegating black Americans who attempted to cosmetically blend in with the white majority–– were liberated by broad social change. Although white-skinned, in a figurative sense–– perhaps I have never ceased applying skin-lightening crème…

Depending on wear and tear–– about once a year I visit a prosthetics clinic to get my mechanical arm serviced. The waiting room magazines have titles such as ‘Thrive’, ‘Amplitude’ and ‘Limb Power.’ I browse them with no less curiosity than that accorded to a ‘National Geographic’ while waiting for an oil change.

Those magazines, I have noted, are partly funded by the prosthetics industry. Often reported are high-tech innovations in both high-tech legs and myoelectric arms. A typical article is that recalled about a robotic hand under development. Operated by brain signals, its fingers can apparently ‘feel’ an object held by its wearer.

That description was a reminder that my fake arm works on technology developed after World War One. What was designed for amputee vets of the trenches–– still works for me. No batteries or brain implants are required…

Those prosthetic clinic magazines also showcase ‘adaptive devices’ for amputees. Most of the attachable gizmos shown are for activities like cycling, golfing or kayaking. The impression given is that the restoration of an amputee’s self-confidence may depend as much on ability to paddle a kayak as on relearning how to button or zipper…

The magazines understandably give more attention to prosthetic legs––quite in keeping with the skewed ratio of lower to upper limb loss. There are ads for designer legs printed with flowers or team-logos. Such options comport with the general encouragement to flaunt the limb difference. Also commonly featured are hi-tech legs for extreme sports. The amputees shown windsurfing, skiing or rock-climbing look fearlessly determined.

Unmentioned in the glossy pages are the costs of these specially designed prosthetics. A high-tech knee for cycling would certainly be cheaper than the carbon fibre sprinting legs of Oscar Pistorius. Still, most prosthetic devices designed for specific sports are well beyond the reach of basic Medicare. Plainly, the world of amputee athletes is in a separate universe from that of old men in wheelchairs with empty pant legs…

Along with the many ads for prosthetics and accessories, the limb-loss support magazines also promote ‘wellness.’ Many of the articles appear to be written by the differently abled themselves. Their advice is especially aimed at newer (of course, involuntary) members of the ‘community’. Along with the standard fare of health and nutrition tips are articles dealing with more sensitive issues–– e.g.: ‘the lowdown on prosthetic liners.’ One issue directs readers to a podcast on ‘limb difference love.’

For those recovering from traumatic limb loss, the mantra seems to be: ‘Embrace the new reality with a hero’s mindset’… That message is reinforced by inspirational testimonials:

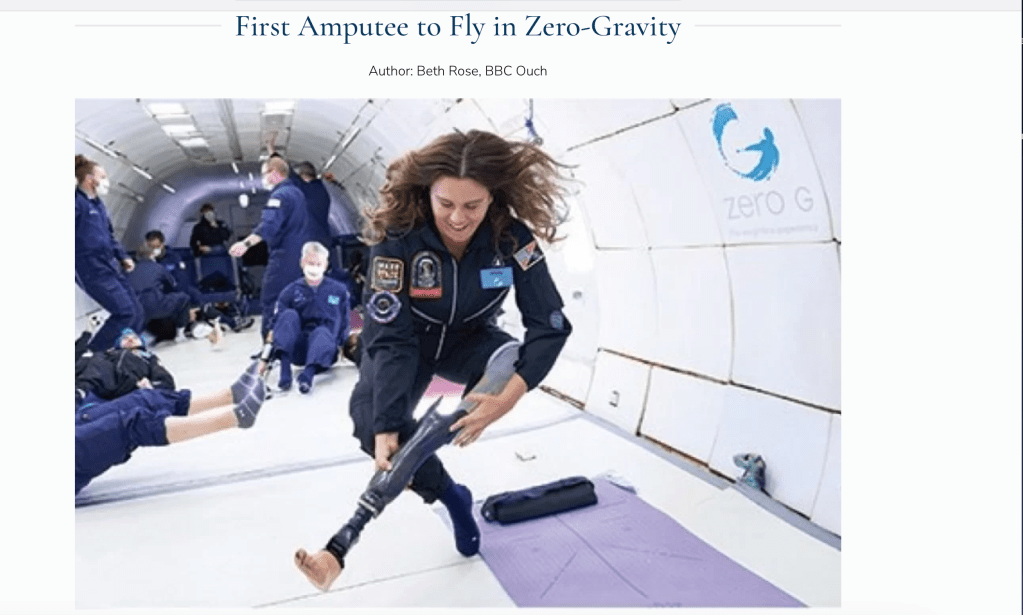

Athletes, musicians, artists and on-line influencers have been featured among the inspirational. The ‘First Amputee in Zero Gravity’ was an attractive female pilot. An Ontario politician was photographed in her office chair smiling broadly. Her bare prosthetic leg stretched out before her reinforced her message: the disabled ‘hero’ has no need whatsoever for wigs, combovers or skin-lightening crème…

My last visit to the prosthetics clinic came just a few days after seeing the Monty Python documentary. In an odd coincidence, the cover story of the ‘Thrive’ magazine on the waiting room counter featured an amputee comedian. For an old man who neither watches TV talent shows nor attends standup comedy performances–– ‘amputee comedian’ sounded rather like an oxymoron… I read her interview with more than the usual interest.

Early fortyish and missing both hands and a leg from birth, CG described herself as having had a “pretty normal” childhood while having been ‘hyper-independent.” The pursuit of comedy, she said, fit naturally with her sense of humour and desire to perform. She has apparently been lauded in comedy festivals and has appeared on national TV in Canada. She mostly performs stand-up comedy––some of it, in her words: “dark and dirty.” The only push-back for being edgy, she claimed, was from among the non-disabled in her audiences. She implied they were uncomfortable hearing a triple-amputee woman joke about sex…

Taking note of her name, I later Googled her. Several YouTube clips were posted of bits from CG’s festival performances. She appears with bared arms and a hand mike Velcroed to the stump of one wrist. The only slightly off-putting element in her performance was the squeaky laugh that sometimes followed her punchlines. She joked about defying the expectations of the non-disabled and reacting to patronizing treatment. In another clip, she spoke of living independently with her cat and having an interesting dating history. In her stand-up, she probably goes into juicier detail…

I continued the informal research by looking up ‘disabled comedians.’ Multiple pages came up with links to You Tube, Instagram and TikTok.

Surprisingly, ‘amputee comedians’ comprised an entire sub-genre. Those video clips were mostly younger American performers, both male and female. Their limb differences ranged from three missing limbs to a few absent fingers. Whether appearing with crutches, prosthetics or bared stumps––all engaged their audiences in full-frontal confidence… Those I watched made light of their disability and joked about dealing with stereotypes. Most of them were salty-tongued and raunchy. They seemed keen to dispel notions of handicapped asexuality…

Still, their acts reminded me of a comment by CG in her ‘Thrive’ interview. She had said that audiences often see disabled comedians as“one trick ponies.” Their jokes are mostly about disability. Yet why is that “stigmatized”, she asked, any more than the shtick of so many female comedians around their sex lives?

That was a fair point. From very limited exposure, however, I had to agree with the one-trick pony critique. Those amputee comedians seen on YouTube were funny and smart. All seemingly sought to ‘educate’ their audiences while entertaining them. Yet apart from their unique personalities (and diverse limb differences)– their routines seemed repetitive. A half-dozen or so short videos was enough to get the general message. I had no interest in proceeding further down the links. Yet those half-dozen videos did cause me to wonder–– not for the first time––why are so many physically disabled people drawn to performance?

Even CG, in her ‘Thrive’ magazine interview, had spoken of her childhood bent to perform. While there certainly are barriers yet to be broken–– disabilities have been increasingly ‘represented’ in a range of performance-related careers from acting to newscasting. There are hosts of motivational speakers who are ‘differently abled’.

Of course, audiences have always adored ‘inspirational’ figures. Some disabled folk are glad to oblige––even as volunteers. Yet other disabled activists (especially the younger) have scorned the public appetite for ‘inspiration porn.’ Not that activism itself is without a measure of performance!

Still, most non-disabled (or rather, presently non-disabled) agree that the ‘coming out’ of disabled people has been long overdue. Yet more recently there has been growing opposition to achieving such inclusion through official policy. In fact, in the USA ‘Diversity, Equity and Inclusion’ programs have been cancelled by the incoming nativist regime. How that will impact society more generally remains to be seen.

Up to the present, most disabled performers have probably benefited from the social trend of inclusivity. The cynical anti-DEI view is that the success of some may have had more to do with their disability than with their talent. Perhaps the disabled performer should respond to that with a middle finger. Those who lack one–– no doubt have alternative gestures that are equally effective.

As for the desire to perform–– I see evidence that it is often driven by goals loftier than self-affirmation and success. Who but the heartless can disdain the longing to be respected for one’s essential humanity?

Not long after viewing the amputee comedians, I came across the US-based ‘Squeaky Wheel’ website. Similar to ‘The Onion’, it consists of satiric ‘fake news’ with accompanying photos. Yet unlike the scattergun satire of ‘The Onion’, ‘The Squeaky Wheel’ is narrowly aimed. According to its chief editor, the website’s mandate is to ‘fight ableism through satire.’ That satire is not only directed at the commonly acknowledged obstacles faced by the disabled. For a younger audience there are multiple satiric reports on dating and sex.

The reports which caught my eye included: ‘8 Signs That You, a Nondisabled Person, are a Victim of Reverse Ableism.’ One of the eight ‘signs’ is: ‘You are not inspirational when you do everyday things.’ There was a little geopolitical commentary in the piece: ‘Kissinger Dies After Lifetime Spent Expanding the Global Disability Community…’ Rather more scathing was: ‘Disabled Dog Receives Better Accommodations than Disabled Human…’

One of the pull-down menus on the site includes an ‘About Us’ section. It listed all twenty-plus writer/editors along with a cartoon portrait and short self-description of each. In the blurbs, each team member describes his/her/their interests and the disability with which he/she/they identify. (Some ‘identify’ as both disabled and LGBTQ). The first impression from site photos was that the team were mostly wheelchair users, but their bio-blurbs revealed disabilities ranging from the physical to the neurological. Incidentally, the deaf and blind ‘communities’ were represented––but not that of the limb different…

Self-descriptions which suggested fragile health were accompanied with tart humour: e.g.: ‘She’s they’ve/ had rheumatoid arthritis for her/their entire life (brag).’ One young woman described herself as: “a social justice non-warrior who is remarkably busy for someone without a paid job…’

Another pull down menu informed that ‘The Squeaky Wheel’ is funded as an NGO which, apart from the website, produces video for TV and internet. Team members also give workshops on comedy writing at colleges for “disability-centered student organizations…” As writers, the team’s activism is not performative in the manner of the disabled comedians–– but their work is probably reaching a wider audience. For its contributors, The Squeaky Wheel’ is obviously much more than a job…

Looking through that website did bring back to mind the comment of John Cleese about “oversensitive communities.” Since that 2013 interview–– might the (now octogenarian) Python have been exposed to some disability comedy? If so––how would he judge its quality?

He would surely get a few chuckles. Even if he wouldn’t grant ‘The Squeaky Wheel’ or disabled stand up comedy to be top-notch–– he would have to agree that the material is neither intended for, nor created by, the easily offended. Indeed, making light of oneself (while challenging stereotypes) seems to be the mainstay of much of the genre… The individual writers and performers may be vulnerable in various ways––but they can hardly be ‘oversensitive.’

In a more general sense, do disabled people regard themselves a ‘vulnerable community’? Many probably do. There is much accord among the severely affected around such practical concerns as public access, health care and endemic poverty. Whether such accord among individuals scattered around the globe constitutes a ‘community’ depends both on one’s politics and use of semantics. While many disabled in western countries may be ‘woke’ (to use the much-maligned term) there are probably quite a few who identify as conservative, religious or even as ruggedly individualistic…

In my brief introduction to ‘disability comedy,’ I also wondered how comedians and comedy writers of that genre would regard some of the old Monty Python skits. Would they be offended by the limbless Black Knight or by John Cleese performing the ‘silly walk’?

If some would take offence–– the insult would probably not be due to over-sensitivity. It would more likely reflect the belief that the disabled can joke about themselves in a manner which the non-disabled ought not to employ. One might use the analogy of black comedians using the ‘N’ word which is justifiably taboo for non-black comedians. In joking about oneself or social group, one has agency and control. As an object of mockery by a dominant group, the ‘marginalized’ are made more vulnerable. Mockery of the vulnerable who are rendered voiceless is mean-spirited and even cruel…

I would defend the Pythons against such a charge. The Beatles of Comedy would never have been deliberately mean or cruel. They satirized snobbery, wealth and power. Undeniably, some of their skits were careless about the reactions of segments of their audience. Perhaps they even thought that if everyone in their audience felt insulted at least once–– their satire was effective. At the same time, it should be noted that the 1960s-1970s were decades before ‘wokeism.’

Finally, in regard to ‘touchy humour’–– I am glad to have come of age when terms like ‘identity’ , ‘community’ or ‘representation’ were not part of the vocabulary. Apart from all the other anxieties of adolescence– it is hard to imagine having to agonize over the labels young people are now pressured to apply to himself/herself/oneself/ itself/themselves. I worry for my little grandchildren who in a few years, will face social pressures yet unknown.

Sometimes it seems a privilege to be old!

-2025, January

Leave a comment