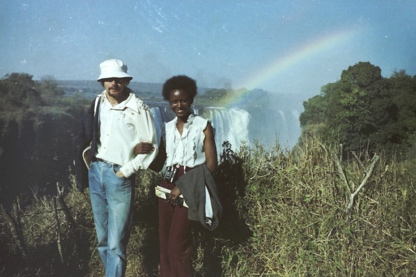

Within a week of marrying in late December 1984, my Zimbabwean wife, T., and I arrived at Heathrow Airport enroute to Canada. The female immigration officer who checked our passports had reddish grey hair and a severe expression. She resembled Maggie Thatcher.

“And what is your relationship?” She glanced stonily between faces and photos.

“Husband and wife,” I said. While I fidgeted, T. craned around for her first glimpses outside Africa.

With a scowl, the officer stamped our passports. As we turned from her booth, I swear I heard from behind, a muttered: “good god!”

Perhaps it is no coincidence that non-white immigration via bogus marriage was among the bitter issues roiling Thatcherite Britain that year. On the other hand, perhaps I had been over-sensitive to that officer’s demeanour. In either case, our brief interaction with her was taken as our first reception as a couple in the wider world. It did not seem auspicious…

Later, on the train into London, through beads of rain I stared out at the dim December landscape. ‘Just what are we taking on?’ I wondered. ‘Can my 22-year-old wife possibly bear up in a cold alien land?’ For her part, T. sweetly squeezed my hand, oblivious to my dark apprehension.

Mercifully, cold anxiety was soon quelled by the warm welcome in Oxford, of a friend who was herself, a refugee from Chile. On New Year’s Day, we flew to Vancouver. Landing in the tail end of a blizzard, we were met by another loyal friend. My old comrade and his wife, native Nova Scotians, hosted us for a week. Even after we rented an apartment, my friend’s wife guided T. through an ‘orientation’ to the strange wintry world. Whatever the public perception of mixed marriages in the 1980s–– my young wife and I were never at loss of support of friends… Family support was a little slower in gelling:

In the months before our marriage, not all of T.’s Zimbabwean clan were at ease with her dating a ‘murungu.’ One of her uncles once angrily confronted me in the local bottle store. In T.’s first attempt to introduce me to her elder sister, we were turned away from her door. Even T.’s mother warned her of the dangers she was courting. Yet when it became clear that our commitment was serious––I was warmly received at the family farm. In every one of our subsequent Christmas visits, a cow was slaughtered for feasting. That was the highest mark of respect…

For my part, the initial suspicions were never begrudged. I well understood that hardly any black Zimbabwean over the age of twenty was without some dark (or scarring) memory of the former White-ruled regime. In Rhodesia, there was never institutional apartheid on the South African model. Instead of the blunt ‘Slegs blankes’ [Whites only] sign in Afrikaans over certain public doorways, there was the notice: ‘Right of admission reserved.’ The wording reflected a more British colonial-style colour bar.

One need not read the early novels of Doris Lessing to gather that interracial intimacy in Rhodesia was socially verboten. Yet breaches in the private sphere––especially between white men and African women–– were not uncommon. The existence of a ‘coloured’ community evidenced an early history of that. With independence in 1980, the old racialist order was officially overturned but the racial chasm remained.

In having ‘coloured’ [i.e. mixed race] relatives in the extended family, my wife’s clan were somewhat more open-minded than many locals. Yet most decisive was the support of my wife’s father. When a clerk initially declined to issue us a marriage licence, Baba Mukwacha paid a visit to the provincial courthouse to work his voluble charm. Afterwards, he persuaded the reluctant judge to perform the ceremony. We were uneasy about having to disappoint his expectation of ‘lobola’ [bride-price] largess–– but deeply grateful for Baba Mukwacha’s intervention.

Still, it was touch and go until minutes before the civil ceremony on December 22, 1984. An hour before our appointment, we were stranded by the roadside outside my rural school, ten kilometers from the Masvingo courthouse. After flagging in vain at the passing buses, we ran back to the school compound to plead for a drive into town. Three colleagues begged off despite my offer to fill their gas tanks. One fellow teacher closed his door with an unmistakable look of shame. His inclination to help was overcome by a fear of complicity in a controversial proceeding.

We finally got a lift from the school principal. The kindly Mr. Mushonga dropped us at the courthouse with barely ten minutes to spare. Accepting no payment, he shook our hands and smiled. More than forty years later, the eyes mist in recalling that act of generosity without which my children may never have come to be…

I did not plan to marry in Africa. At the time I sent out the application for a teaching placement in Zimbabwe, I was waiting for a response from the Ministry of Education in Bangkok. In January 1982, one of first pieces of mail forwarded to my Zimbabwe school posting was an official offer of a position at a school in Chiang Mai. Had that letter arrived before I had left Canada, perhaps the maternal root of my progeny would have been grounded in very different culture…

So, it was not quite by design that I ended up in Zimbabwe in my early thirties. By then, I had already spent seven years in Africa. I had stayed in different communities long enough for their ways to cease seeming exotic. By 1984, the ambiance of Mashonaland had taken on a comfortable ordinariness. I had never cut myself off from fellow expats but came to prefer the company of locals. Meanwhile, the approach of my middle thirties stirred a desire to settle down. If I were to have children, I did not want to be a grandfatherly father. While I was not panicking––I was certainly aware of a closing window of opportunity.

It was then I was smitten by a young student teacher. We met at the edge of Masvingo town waiting for a bus. In our chat, I found out her younger brother was one of my students. I invited both for tea. Within a few weeks, we were spending every weekend together. Within a few months, we decided to marry.

Just before our marriage, I suspended my long-standing diary keeping habit. I felt that daily reflection could interfere with the adaptation to married life. Too well, I knew how anxieties expressed in ongoing journal narrative tend to grow darkly self-fulfilling…

Our first venture of living in Canada in 1985 lasted only seven months. With the sudden departure arrangements from Zimbabwe, my wife had to enter Canada on a tourist visa. She could not register for classes nor did she qualify for Medicare. Meanwhile, tentative about career plans, I took two semesters at the local university. When T. became pregnant, the absence of health care benefits became more dire with every advancing month. By July 1985, it seemed I had no better option than to return to Zimbabwe for another secondary school teaching contract.

Our daughter was born in Harare in September 1985. A second daughter followed two years later. At the end of my three-year contract, T. was deeply conflicted about returning to Canada. She was persuaded to undertake the immigration process not for her own benefit–– but in the hope of a better future for our girls.

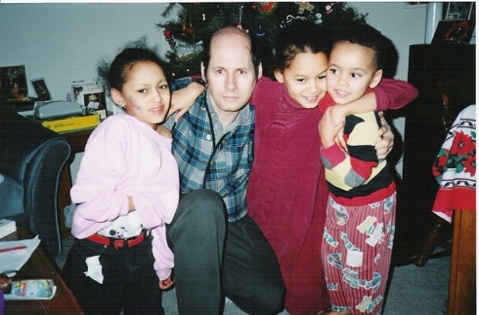

In August 1988, we arrived in Vancouver with little savings and no job prospects. After five nightmarish months without income, I found a job teaching English to new immigrants. Although that employment would remain insecure for years––we hung on. Nearly four years thereafter, we had a son––our only child born in Canada…

As a mixed couple in suburban Vancouver in the late 1980s, we often felt ourselves subject to curiosity. That observation is largely based on reactions in buses and malls. In accordance with Canadian politeness–– stares tended to be furtive. In catching any––I usually returned a cold glare. Still, when shepherding our little girls in public, we were most likely to receive patronizing smiles…

By the time I resumed my journaling habit, there was a wealth of poignant details to record. The best of my chronicling of fatherhood and family life is perhaps the only legacy of real value to be left for grandchildren. Yet interspersed with descriptions of contentment are stark details of vulnerability. A few examples:

Once in 1985, when T. was pregnant with our first daughter, we were walking to a bus stop in Port Moody, B.C, when a male voice from a nearby balcony called out: “Hey buddy, you must have some whopper of a dick!” Not yet familiar with Canadian slang––T., fortunately, did not catch the taunt…

When we returned to Canada in 1988, we first lived in a low-income apartment block dominated by fellow immigrants and single mothers. My wife and I took turns taking our little girls to the play area. I was there with our older daughter one afternoon when a little feral blond girl suddenly spat on her. As I swooped over to pick her up, wailing, other white kids stood by passively. Could it possibly have been a coincidence that my child looked ‘different’?

In the same neighbourhood, a driver once blared his horn as we passed before his car in a cross walk. Due to our little girls holding hands between us––we were apparently crossing too slowly for him. From his open window, he yelled: “Get those fuckin’ half breeds out of the way!”

We were too shocked to react in time to copy the licence plate…

After we moved from that neighbourhood, I sometimes returned to the barbershop in the local strip mall. The last time, I brought along my 4-year-old son. While cutting his hair, the barber launched into a strange conversation with his partner, who was sitting idle in the adjacent chair. The topic was the care and breeding of horses.

“You gotta be careful with cross breeding,” said the standing barber with a chuckle. “You can get some real knot-heads!”

‘Knot-heads?’ Perhaps the barber was innocently talking about horses. Or perhaps he really had made a vile racist slur about my son. Unsure about malicious intent–– I said nothing. I neither told T. about the incident lest she burst into the barber shop, tongue blazing. That was the reaction which I could only imagine.

Well before the coining of ‘microaggression,’ T. was never inclined to let any racist insinuation go unchallenged. She could be a she-bear–– especially in defense of our cubs. My inclination was to avoid confrontation. I assumed that racists, like the white-trash driver at the crosswalk, tend to be violent. What I regarded as prudence–– my wife took as timidity…

In those first years, T. would often complain of some patronizing or belittling encounter. In listening, I would sometimes think she was over-reacting. Yet over-sensitivity to racism was not unexpected for someone who grew up in Rhodesia. Moreover, I well knew that multicultural Canada can be a cold and hostile place for newcomers struggling with settlement. Yet how could someone who worked with immigrant students ever be wanting in sensitivity to his immigrant wife?

Although we often reacted differently to manifestations of it, T. well knew that I abhorred racism. Yet unlike her and countless others––I am inclined to question why ‘race’ need be a primary feature of self-identity. However provocative that may seem to those who take great pride in racial identity–– I have long questioned the very categorization of ‘race.’

Whatever insights or epiphanies dare be claimed though experience, I do recognize that my attitude to ‘race’ is somewhat traceable to childhood. I grew up in a Canadian village where everyone was white. Because there were no outliers for comparison, ‘whiteness’ was never a category of belonging. Of course, without resort to Sociology #101, I recognize that that absence of racial awareness was an ‘in-group’ privilege…

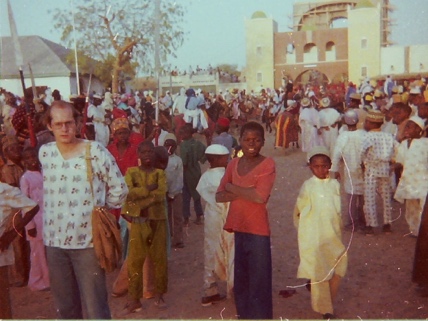

In any case, the first time I experienced being ‘white’ was in the 1970s in Northern Nigeria. I had previously been a ‘gringo’ on the ‘gringo’ trail–– but that was transitory. In Hausaland, I lived for two years in a school community in which everyone except me was black or brown.

At first, it was embarrassingly difficult to remember my students’ names. Every face looked the same. Yet within a few months, I began to perceive varying shapes of noses and ears, distinct expressions and varying shades of complexion. Nigerian faces came to look quite as distinct as ‘European’ ones….

Sometimes I would go weeks without seeing another white person. Once a team of school inspectors arrived from Kano city. Before seeing any–– I knew there were whites among them. That was detectable by a peculiar odour wafting in through the open door of the staff room. Sure enough, that olfactory signal was followed by the entry of a red-faced elderly Brit. To my then-acculturated nostrils, ‘bature’ sweat smelled ‘abnormal…’

Some Nigerian colleagues who had not travelled abroad, were curious about the features that tend to accompany pale skin. It was jokingly observed that my eyes were the colour of a cat’s. Once a Igbo friend (himself a stranger in Hausaland) asked whether my hair was as fine as it looked. He innocently asked for permission to touch it.

There were so few whites in that corner of Hausaland, that several times I was mistaken for some other ‘bature’ who looked utterly different from me. One would suppose that a missing arm would have made me particularly identifiable. Yet it was white skin by which I was primarily perceived…

I would not suggest that having been a sole ‘bature’ in a Hausa school community in the 1970s was a similar experience to my wife’s having been one of the few Shona immigrants in suburban Vancouver in the 1980s. She faced challenges I have never known. Yet I would claim that my experience in Northern Nigeria imparted a powerful insight. That is–– that ‘race’ is primarily a social construct determined by subjective perception.

It is well established that in human genetics there are no distinct racial types. Like the reflected colours of a prism, the superficial variations (skin tone, nose shape, hair type, etc.) among people are blended and continuous. Anyone who travels overland through Europe to Asia, or northwards from tropical Africa, will have observed that. The transition in skin tone and facial features of local inhabitants is very gradual.

The absence of a distinct genetic basis of ‘race’ is not to deny that traits associated with ‘racial types’ often predominate in perception of human differences. There is little mystery as to why that tendency has endured from time immemorial. Plainly, perception and categorization by ‘race’ is freighted in history, power and social dominance…

In America, any trace of Black African ancestry all but impels one to identify as Black. Many historians have noted that racial assignment in America is primarily due to perpetuation of the “one-drop rule”–– the legacy of slavery. After the cross-Atlantic slave trade was banned, the continuing slave economy in America needed to rely on the local slave population for replenishment. An increasingly broader categorization of ‘blackness’ was thereby required. While the categorization was imposed: due to shared marginalization–– the Black American identity was historically adopted and embraced…

By contrast, racial classification in Brazil evolved very differently. Despite a similar legacy of slavery, the perception of ‘black’ and ‘white’ tended to be tied more to class and wealth. Many Brazilians who would be considered Black in the U.S. both consider themselves–– and are seen by other Brazilians–– as White.

Racial perception in Canada tends to follow the American model. I make that broad generalization not on scholarly authority but on personal experience. Both Canadian friends and relatives have remarked that my daughters closely resemble their mother (That was always intended– and taken– as a compliment).

In Zimbabwe, however, my children are said to look like me. That was often commented by T.’s sisters in response to photos sent over the years and repeated during our family visit in 1998. The late sukuru [grandfather] Mukwacha thought his grandson (my son) so resembled his baba–– he kept addressing him by my name…

Such contrasting perceptions are obviously not divorced from culture and history.

I recently searched the origin of the term ‘miscegenation’ in Wikipedia. Apparently, the ugly word first appeared in the title of a pro-slavery propaganda pamphlet published during the American Civil War. ‘Miscegenation: The Theory of the Blending of the Races Applied to the American White Man and Negro’ (1864). It was a bogus advocacy of interracial marriage falsely claimed to have been written by a northerner. The intent, of course, was to infuriate white southerners to fight even harder for their “righteous” cause…

In the early twentieth century, “the evils of race mixing” were intertwined with the pseudo-science of eugenics. Selective human breeding in pursuit of Aryan “racial purity” emerged as a key tenet of Nazi ideology. While eugenics was not quite so brutally codified in North America (forced sterilizations, notwithstanding), the safeguarding of white supremacy was a fact of everyday life.

An article recently come across in an old ‘Life’ magazine shockingly reveals mainstream America’s fear of interracial mixing in the pre-World War Two era. The article bemoans that the vast resources of a potential “United States of Brazil” are wasted on its underserving inhabitants.

To quote: ‘Brazilians are a charming people but incurably lazy… The Portuguese conquistadors did not bring their wives but married Indian aborigines… Their descendants added the blood of negro slaves to the strain. The mixture did not work.’

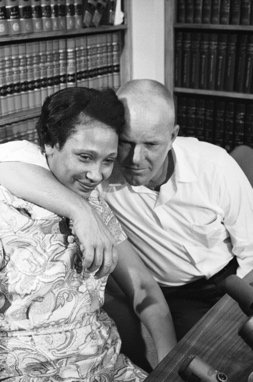

Interracial marriage was banned in forty-one U.S. states until the 1940s. That ban was a reflection of prevailing attitudes in both former slavery and non-slavery states. It was still prohibited in sixteen states until 1967. Only then was the ban struck down by the Supreme Court during its brief interlude of progressive legislation.

Historical attitudes to interracial intimacy in Canada were only marginally more tolerant. Little more than a generation ago, White women were typically stigmatized for dating Black men. Well into the 1940s The Ku-Klux-Klan had active Canadian chapters. High on their targets for intimidation were couples considering mixed marriage. In 1939, in violation of a law not repealed until the early 1960s, a White woman in Ontario, was convicted and imprisoned for pregnancy by a Chinese man. Fortunately, Velma Demerson lived to be commemorated for her courage…

In the midst of the current backlash against ‘wokeism’ –– it is sobering to be reminded of such history.

All the progress made in the last two generations toward acceptance of diversity is now threatened with reversal. Throughout the world, reactionary movements are either in power or on the march. The favourite target of nativists in America and Europe is immigration from the global south. Far right “influencers” warn of a “great replacement conspiracy” whereby western civilization itself is threatened by ongoing “dilution” of the already narrow White majority. Trump himself delights his MAWA (‘Make America White Again’) faithful with obscene rants against allegedly unassimilable immigrants from “shithole countries…” Such blatant racism harkens to the racial purity and eugenics advocacy of the not-too-distant past…

Still, there is hope that the nativists can no more change the course of history than King Canute could command the tide. Even if the authoritarian regimes of the present do succeed in halting non-White immigration–– demographic change is already in motion. By birthrate alone, the western world will enviably become ever more multicultural and ethnically blended…

When anti-miscegenation laws were struck down in America, barely 3% of marriages were interracial. Google informs that in 2019, about 19% of marriages in America were interethnic or interracial. A particular jump has been noted in mixed Black and White couples. In Canada, the rise in mixed-race marriages has been even greater. In 2022, about 36% of all new couples were reported to be of mixed ethnic or racial origin. A deracinated world of blended humanity may already be emerging…

I proudly note that all three of my children can be counted in the statistics. In their marriages, they have further enriched the heritages of subsequent generations by bringing Italian Canadian, Byelorussian Canadian and Japanese Canadian into the mix. Regarding their own ‘racial’ identity– hopefully, they can always be free to embrace their dual heritage. Hopefully, they will not feel pressured to make a binary choice…

In the late 1990s, cracks in the union between T. and I widened to fissures. In 2001, our marriage split apart.

Our marriage did not fail because of disparity in culture, extended family pressure or tensions over money. Those supposed strains of a mixed marriage were not the cause of our breakup. What was irreconcilable, rather, was the gap in our ages. As I grew to early middle age, T. was just reaching her prime. She longed for opportunities lost. As the eleven years between us seemed to widen–– we ever more bickered and clashed. Like gradual lead-poisoning, the level of toxicity climbed…

At one torturous moment in the fracture, our eldest daughter bitterly asked me: “How could two people so unhappy together ever have married in the first place?” I had no answer for our then-rebellious teen.

Even friends may have wondered about the basis of the relationship between T. and I. To many, our marriage probably appeared typical of many between an older white native and a younger non-white immigrant: unequal but transactionally convenient. But our marriage was never one of convenience. T. was not looking to emigrate from Zimbabwe nor to bring wealth to her family. In the beginning, undeniably, there was ‘inequality’ which T.–– through education and dogged striving––gradually overcame. Even in the bleakest turns, I never doubted that our relationship was initially born of mutual attraction…

Among the poignancies of our first months, I particularly recall a Friday evening when T. failed to show up for the weekend, as planned. Knowing that she was under pressure to stop seeing the murungu, I feared the worst. By Saturday afternoon, I was in full despair. Then near dusk–– her knock came softly on the door. As we embraced, T. moaned out her story. Without any means of transportation from her remote school, she had walked ten miles to catch a bus. She was dishevelled and her feet were swollen. In clinging together there in an open doorway––I knew we would marry…

That was just one of many recollections with which I might have reassured my teenage daughter in that dark moment of family break-up. I might also have told her about our first Christmas in Canada in 1988. Just three years old, she picked out our Christmas tree from the lot beside the bus loop. She said it looked “sad.” I was relieved that it was the cheapest one in the lot. With her little sister in T.’s arm, we dragged the scrawny tree five blocks to our tiny apartment. In decorating it, we managed to fill the bare patches. That was just one of many days we were a vulnerable––but happy–– family…

Admittedly, T. and I and were never ‘soulmates’–– but how many couples ever really are? We were probably not as close as the Lovings–– the celebrated Virginia couple whose case overturned the ban on interracial marriage. But we were a loving family.

Even in the shared custody that followed separation–– the mutual devotion to our children of T. and I never faltered. All three, gifted in her/his own way, grew to be fine adults. Nearly a quarter century after separation, we share in immense pride in our children and grandchildren. With our new partners, we regularly come together for family celebrations.

By what greater measure can a marriage be deemed to have been a success?

Just a few months ago, I welcomed my fourth grandchild–– the daughter of my son and his partner. On her mom’s side, her ancestry is Irish and Japanese. The Shona and British stock on her dad’s side is the genetic contribution of my ex-wife and I. With such a rich heritage and with two highly educated and devoted parents–– that little girl is truly a cosmic lottery winner…

In looking for the first time into her sweet face, I trembled with immense gratitude. Among my thoughts, oddly enough, was a memory from the day her grandmother and I married. I thought of the moments of panic while we were stuck by the roadside, an hour before our appointment at the courthouse:

After several buses roared by without stopping, T. suddenly cried out:

“This is a bad sign. Maybe my vadzimu [ancestors] are warning me. Maybe my ambuya [grandmother] is not happy!”

I knew T. adored her late maternal grandmother. While attending high school, she has lived with her in the cottage of her ‘coloured’ aunt in the town of Fort Victoria (renamed Masvingo after interdependence). T.’s grandmother had had a rough life. She bore three daughters by a ne’er-do-well Scotsman named Wilson, before returning to her Tribal Trust village. There she bore another daughter, T.’s mother, by a Shona man. She was ostracized by many in her village and never accepted in the white town of Fort Victoria…

It was probably in view of the old woman’s life-long strife–– caught between two worlds–– that T.’s mother had first warned T. against marrying a murungu…

“Maybe we’re rushing into this,” said T. in a breathless moment at the roadside.

Yet as fate would have it––Mr. Mushonga drove up moments later and delivered us to the courthouse…

With the fait accompli of our marriage––T.’s gentle mother warmly accepted it. I always felt welcome at the farm. Although she spoke little English and I very little Shona–– she could not have been kinder to me. In the years before we moved to Canada, she came to stay with us at few times at our place near Harare. In those visits, Ambuya Mukwacha delighted in taking care of our little girls.

Decades later, soon after the death of her husband, she came to Canada for the wedding of my second daughter (one of her several granddaughters). Ambuya was in her eighties, and it was her first trip in an aircraft. She amazed all who met her with her spryness and curiosity.

Unwilling to stay idle, one day she insisted on being taken to a local blueberry farm. She apparently spent the day picking along with a crew of labourers. With the proceeds of that work, she bought my son a family bible…

Admittedly, I do not share the religious faith of my former wife, T., her late mother– nor that of my adult son. Still, I could not have been more pleased that my new granddaughter was given the name of her great-grandmother–– my son’s beloved ‘ambuya’…

-2026, January

**********************************************************************

Poem: ‘At the Graveside of Henry Wilson’ (1987)

OPEN:

👍🏼 😐 😬 🥱 👎 💩

Leave a comment